The influence of redistricting today on political competition can be seen most clearly in the dramatically opposite arcs of two states, Pennsylvania and California.

In Pennsylvania, the Republican party, which controlled both legislative chambers and the governorship, used its remapping authority to turn what had been a highly competitive congressional map over the previous decade into one with virtually no competitive contests.

Meanwhile, a continent away in California, voters approved a pair of ballot measures that entrusted redistricting to a bipartisan commission and established a primary system in which the top two finishers, regardless of party, advance to the general election. The combination of these changes have turned the page on a sleepy decade of uncompetitive races and made the Golden State one of this year’s top congressional battlegrounds.

Reasonable people can disagree about the best way to redraw congressional lines, which is a constitutionally mandated task entrusted to states every 10 years after the Census Bureau releases new population figures. But the divergent experiences of Pennsylvania and California since 2010 demonstrate that the process used can make a huge difference.

To fully understand the context, let’s go back to 2005, when I wrote a column for Roll Call that sought to determine which states had produced the most competitive congressional races per capita over the previous three campaign cycles.

Using independent handicapper Charlie Cook’s House race ratings for the 2002, 2004 and 2006 cycles as my guide, I determined that Pennsylvania had the most competitive U.S. House seats per capita of any state during that period. By contrast, California had the second-least number of competitive races, trailing only Massachusetts.

For this column, I decided to update my research. This time, I didn’t do a full national comparison; instead, I looked at Pennsylvania and California alone. I compared the number of competitive U.S. House seats in 2008 and 2010 (that is, the last two cycles under the old lines) to the number in 2012 and 2014 (the first two cycles under the new lines). As I did for the Roll Call article, I deemed a contest “competitive” if it had a Cook rating of tossup, lean Democratic or lean Republican.

In 2008 and 2010, Pennsylvania played host to a combined 11 competitive U.S. House races. By contrast, the state has produced just two competitive contests under the new lines. And while 37 percent of the seats in the Keystone State’s delegation were competitive at least once in the 2008-2010 period, just 11 percent were or are competitive in 2012-2014.

In California — which has the nation’s largest congressional delegation at 53 seats — just seven races were competitive in 2008-2010, a figure that doubled to 14 in 2012-2014. And while 11 percent of the California delegation’s seats were competitive at least once in 2008-2010, 19 percent were or are competitive under the new lines.

To better understand how different redistricting processes can make or break a state’s competitiveness for congressional seats, let’s take a closer look at each state.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania uses a traditional, state legislator-driven redistricting system. With the GOP in control for the past two Censuses, they’ve worked to draw the most favorable lines that they could for their party. While the effort didn’t work so well after the 2000 Census, the post-2010 remap has worked like a charm.

In 2000, GOP redistricting honchos had high hopes for a strongly Republican map, and initially those hopes came true. Right before the 2002 election — the final year of the post-1990 map — the delegation’s split was 11 Republicans to 10 Democrats. Due to population loss, the state dropped two seats between 2000 and 2002, but after the 2002 election — the first under the new lines — the GOP lead had expanded to 12-7.

Just two years before that, Pennsylvania voters had given Al Gore a five-point victory, so dividing so many Gore voters into districts that produced a 2-to-1 GOP edge in House seats was no mean feat. Indeed, to gain the upper hand, the mapmakers had to spread Republicans too thinly to create safe seats. Over time, the party’s advantage eroded in these places, making the seats ripe for Democratic pickups. Such GOP incumbents as Phil English, Melissa Hart, Don Sherwood and Curt Weldon went down to defeat, in some cases after surviving stiff competition for a cycle or two. “The whole attempt was an exercise in Republican overreach that really didn’t work from the beginning,” said Kirk Holman, a one-time Republican official in western Pennsylvania.

Two additional factors shaped Pennsylvania’s high degree of competitiveness in the 2000s.

First, as the post-2000 maps were being hashed out, the Democrats’ main goal — and a goal Republicans were copacetic with — was the safeguarding of Rep. Jack Murtha, whose seniority had produced a vital stream of federal revenue into his blue-collar corner of Western Pennsylvania. “The map was worked backwards for keeping Murtha safe,” said Democratic strategist Larry Ceisler, who was an expert witness for the congressional Democrats in the 2000 redistricting litigation. “Murtha made a deal with the GOP to do that, in which he had to deliver enough Democratic votes in the state House to pass the plan.”

But the need to shield Murtha cut down on the options for drawing lines in other districts, and the borders around some districts got “a little too cute,” Ceisler said.

This brings us to the second factor that aided competitiveness in the 2000s: The breakdown of Pennsylvania’s unusual relationship between party affiliation and ideology.

Historically, the suburbs of Philadelphia have been notable for their socially moderate strain of Republicanism, while the region around Pittsburgh has been known for a surplus of economically liberal but socially conservative Democrats. In the 2000s, voters in both regions began migrating to the party that more closely fit their ideology on social issues — that is, the Philadelphia suburbs became notably more Democratic, and Western Pennsylvania became more Republican. The confluence of a rapid partisan realignment and a lot of potentially competitive districts produced a surplus of volatile seats during the decade.

Superficially, the post-2010 redistricting could have turned out like the post-2000 remap. For the second decade in a row, the GOP controlled the legislature and the governorship, and party leaders put forth a map designed to produce a GOP congressional edge that contrasted sharply with the state’s continued Democratic drift in presidential politics. (In 2008, the last election before the new lines were drawn, President Obama had doubled Gore’s margin, winning the state by 11 points.)

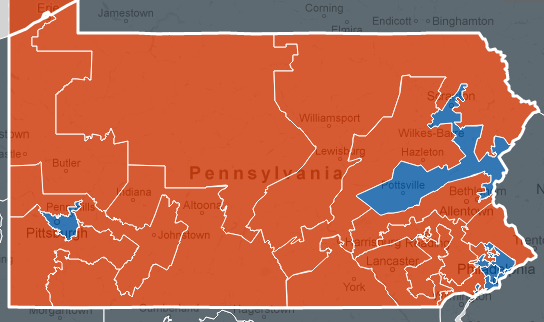

This time, though, the legislature and GOP Gov. Tom Corbett did a much better job boosting their party’s chances, crafting lines with such precision that the delegation’s partisan breakdown is now 13 Republicans to five Democrats. “The Republicans drew circles around the Democratic enclaves and then carved up the balance of the state to minimize the random Democrats who happened to reside outside the cores,” said David Patti, the president and CEO of the Pennsylvania Business Council. “The result is five really strong Democratic districts and 10 or 11 pretty darn safe Republican districts, leaving two or three seats possibly in play.”

Terry Madonna, a Franklin & Marshall political scientist, called Pennsylvania’s post-2010 redistricting “one of the most effective in the nation.” Madonna said the Republicans “gave up any chance of ever winning” the 17th district now held by Democrat Matt Cartwright in order to protect the 6th, 7th, 8th, 11th and 15th districts. Those seats are held respectively by GOP Reps. Jim Gerlach, Pat Meehan, Mike Fitzpatrick, Lou Barletta and Charlie Dent, each of whom either succeeded a Democrat or faced a series of strong Democratic challenges under the previous map.

In interviews, political experts from across the ideological spectrum agreed that the Democrats’ chances of ousting a Republican incumbent in 2014 — a low-turnout, midterm election year — are low. One of the Democrats’ biggest hopes for a credible challenge — a rematch between former Democratic Rep. Mark Critz and the Republican who beat him in 2012, Keith Rothfus – fizzled recently when Critz decided to run for lieutenant governor. There may end up being not a single House seat that’s genuinely competitive for either party in 2014.

“There are only a few seats [under this map] that can be competitive, but only in particular years and probably only if there are no incumbents,” Ceisler said. “And even those would take special circumstances.”

California

Following the 2000 Census, California’s Democrats and Republicans collaborated on a status quo map that entrenched incumbents of both parties. And it worked: Over the course of a decade, just a single seat changed partisan hands.

Then, in 2010, voters by a 3-to-2 margin approved a ballot measure backed by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger to create a 14-member Citizens Redistricting Commission that had to draw lines without factoring in partisan data or incumbents’ homes.

“Chosen by a byzantine application and lottery selection process, the commission included a chiropractor, a bookstore owner, and a businessman who just happened to be director of the U.S. Census Bureau under presidents Nixon and Ford,” wrote the Cook Report’s redistricting guru, David Wasserman. “After months of tedious meetings and mountains of public testimony, the commission in August 2011 adopted a new Congressional map that radically — and more logically — rearranged the state’s 53 seats.”

Ironically, the map ended up helping Democrats more than Republicans: The Democrats seized four additional seats to achieve a lead in the delegation of 38 to 15. But these topline gains for Democrats obscure just how much political competition blossomed in the state beginning in 2012.

The new lines put 27 incumbents into 13 districts while establishing 14 new districts without an incumbent — a strong recipe for political competition. Three Democratic incumbents and four Republican incumbents retired rather than run in unfamiliar territory. Even the incumbents who did decide to run again had to introduce themselves to new voters, thus giving challengers an opening. Ultimately, seven incumbents lost bids for re-election.

“The end result was the most upheaval and loss of seniority California’s delegation has ever seen,” Wasserman wrote. “What incumbents viewed as seniority, many voters saw as entrenchment, and reformers got the burst of competition they wanted.”

Further jumbling the political landscape was the new, voter-approved system in which the top two finishers in an all-party primary advance to the general election. Two candidates from the same party advanced to the general election in no fewer than eight districts in 2012. This meant that even in safely Democratic and Republican districts, there was competition — perhaps between different ideological wings of the same party.

In theory, there is no guarantee that the upheaval of 2012 will produce a pattern in which seats are competitive year after year. But those who appreciate political competition have to be at least reasonably happy about how the 2014 election cycle is shaping up.

Currently, the Cook Report has one California seat leaning Republican, two seats leaning Democratic and three listed as tossups. While six competitive seats in 2014 is a smaller number than the eight competitive seats Cook rated in 2012, that’s not surprising — the first year after a redistricting process is always the most volatile.

At a time when some political observers are bemoaning the rise in safe seats in the U.S. House, California is finally doing its part to produce competitive congressional races. For that, political handicappers (myself included) send their thanks to Golden State voters.

—-

Reposted with permission from Governing Magazine.

Larry Ceisler is a part owner of PoliticsPA.

10 Responses

I am beside myself here and incredulous that this article isn’t getting more play. It’s the best article I have read on the subject in years. Bravo Jacobson. I am familiar with the redistricting problem and knew something of the California solution. I had not however heard of the ‘top two finishers’ idea and I really like it. We’re all familiar with the increasing polarization in Congress. The result of this ‘top two’ idea would be sending more moderates to DC. Imagine if every state were sending more moderates to DC from both parties. The impact would be a more congenial atmosphere there; one where building consensus isn’t something lawmakers avoid for fear of getting primaried. No it doesn’t solve the money problem, the PAC problem, or the opportunity cost of time spent fund raising problem. But this idea has potential. Again good work Jacobson. Keep it up.

Author misses key point….why are we continuing to lose population/seats and therefore influence? Answer: we still use antiquated compulsory dues system in PA when other states have given their workers freedom and are attracting people to move there. http://mediatrackers.org/national/2013/08/21/americans-vote-with-their-feet-flee-forced-unionism-states

Using Cook ratings as the only factual proof of gerrymandering is quite possibly one of the most intellectually dishonest analyses I have ever seen. Cook ratings aren’t focused on demographics, but are instead determined by the probability of an electoral victory. Ratings improve based on a number of factors beyond just district demographics, including name recognition, incumbency, favorability, and fundraising.

If Cook Rating was proof of gerrymandering, the seats held by currently safe Democrat Steve Israel of NY and Republican Frank LoBiondo (whose districts have PVIs of “Even” and “D+1” respectively) should be considered “toss ups”.

I think the law should require a starting point every ten years– like start in the northwest corner, make squares based on population, and then make adjustments for geography, county boundaries, etc.—that would be the intial plan to work from

McGinty in the 7th!

Really well done. This is great stuff, and I for one would like to see more of this on PoliticsPA. Editors take note!

I assume you mean Brady, Fattah and Doyle, but otherwise your point is well taken.

In PA7 a good female candidate would destroy Meehan in ’14. We just need to find that person.

In pa7 a credible Dem could surely give a brain dead hack like Meehan a run for his, admittedly endless, money

The Republican held seats are quite competitive…

Cook PVI (R v. O 2012 per Daily Kos):

PA-6: R+2 (50.6 – 48.1)

PA-7: R+2 (50.4 – 48.5)

PA-8: R+1 (49.4 – 49.3)

Philadelphia’s three representatives take a bulk of the Democratic vote in the region:

PA-1: D+28

PA-2: D+38

PA-13: D+13

The reason why the numbers are so distorted is that Democrats are excessively concentrated in small geographic areas in Pennsylvania. No changes to reapportionment can make up for the fact that the cities are 75 % to 80% Democratic. In 2012, there were 59 divisions in Philadelphia that didn’t count a single Romney vote. http://mobile.philly.com/news/?wss=/philly/news/politics/&id=178742021&viewAll=y Given that congressional districts must have geographical boundaries, it’s not hard to understand that Democrats are at a disadvantage when it comes to redistricting because there are only so many ways that you can split up D+90 voting districts. The margins in rural and suburban precincts are much less substantial.

To illustrate my point, if you remove Philadelphia and Allegheny counties from the vote totals for PA, Romney wins by approximately 6 points (53-47). Since these two counties are almost entirely represented by Democrats Brady, Fattah, and Kelly, it’s not surprising to see that the outcome of the remainder of Pennsylvania’s congressional delegation.